NASA has faced mounting challenges regarding the maintenance and efficiency of its expansive infrastructure, which has grown increasingly aged and costly to manage. Historically, NASA amassed 38 rocket engine test stands across six sites within the U.S., many constructed during the Apollo and Space Shuttle programs. However, due to a significant industry shift towards private space exploration companies like SpaceX, many of these test stands are now underutilized, with projections indicating only a fraction will be operational by 2026. The agency’s inspector general highlighted this issue, revealing a broader spectrum of challenges stemming from an aging facility network and a resistance from Congress to implement necessary cuts or closures, primarily motivated by job preservation concerns within the districts that house these facilities.

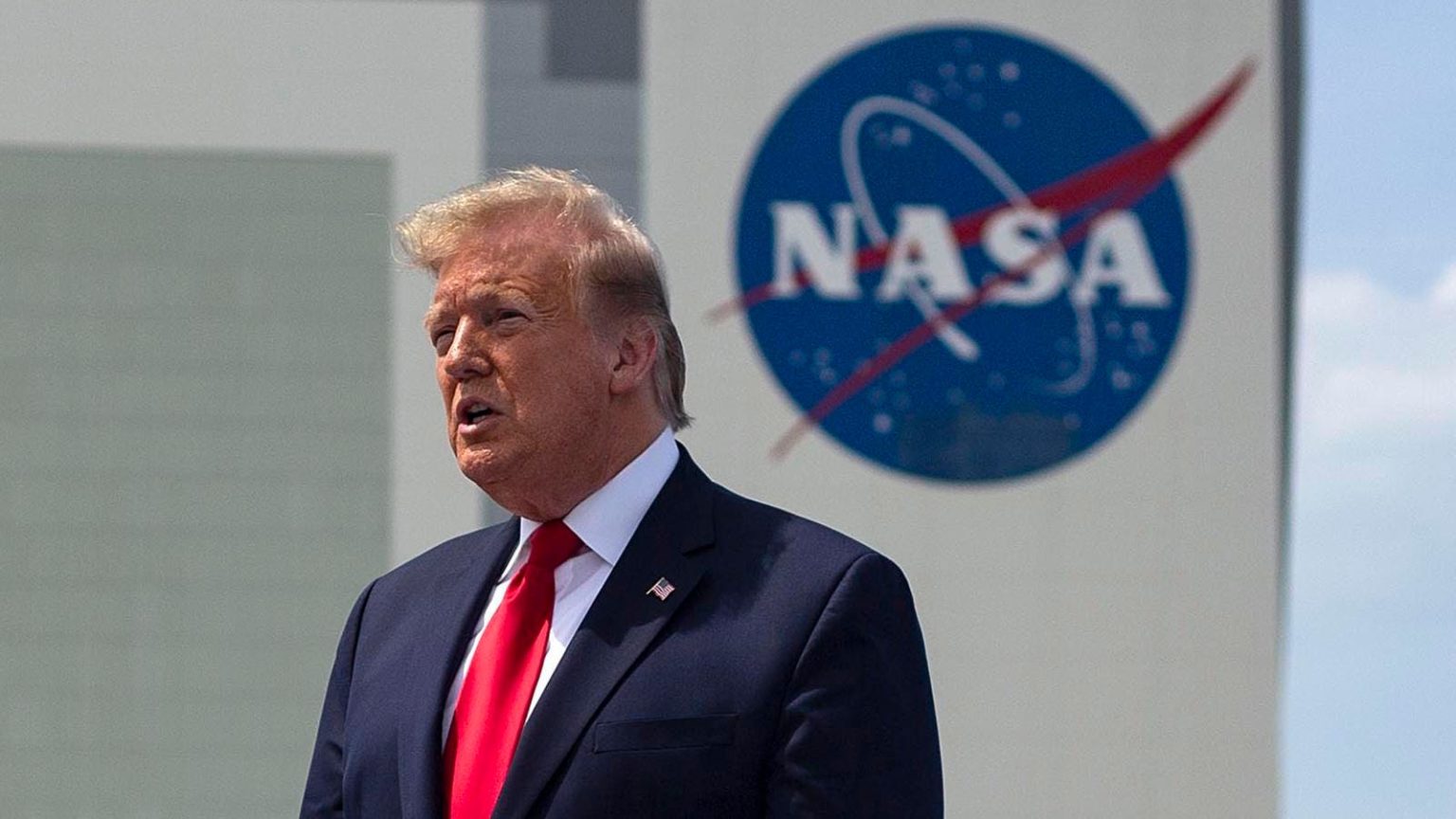

With Donald Trump potentially returning to the White House advocating for substantial government spending cuts, there may be renewed efforts to tackle NASA’s burgeoning operational inefficiencies. Former Republican leaders have signaled that this administration might break the long-standing political impasse surrounding NASA’s infrastructure, including its ten major field centers, some of which are viewed as redundant and costly. Voices within Trump’s transition team have suggested that the agency could benefit from consolidating operations by examining the viability of closing several underperforming centers, recognizing that NASA’s workforce can exceed 19,000 civil servants and 50,000 contractors.

NASA’s extensive physical infrastructure, estimated to be worth $53 billion and occupying 134,000 acres nationwide, has become burdensome for the agency to maintain financially. Much of the infrastructure was erected in the 1960s, and approximately 83% has surpassed its expected operational lifespan. Deferred maintenance has reached over $3.3 billion and is projected to increase. As the agency grapples with these challenges, the aging facilities are not only financially draining but also detract from NASA’s ability to attract top talent, as highlighted in a recent study by the U.S. National Academies of Sciences, indicating that many laboratories are unsuitable for modern operation. The myriad of NASA’s facilities has also led to redundancies; for example, an earlier report identified duplicative capabilities across various centers, thereby signaling a need for reassessment.

Despite the growing recognition of the need for structural changes to NASA’s facilities, attempts to implement such measures have historically encountered significant pushback from Congress. Leaders of the agency in the past, including Mike Griffin, have noted that closing major facilities is politically impracticable due to the strong advocacy of job protection by congressional representatives in affected districts. Earlier efforts, such as a 2005 internal NASA study that suggested consolidating operations at several key sites, failed to materialize, leaving many underutilized facilities operational in contradiction to financial sustainability goals.

To overcome current obstacles, proponents argue that establishing a bipartisan committee similar to the Base Realignment and Closure commissions, which successfully orchestrated military base closures, could be a potential pathway forward. However, some experts caution that NASA’s smaller scale makes such diversification more challenging due to fewer operational options to negotiate or justify closures. The incoming Trump administration, which is likely to explore further efficiencies as part of broader budget cuts, could find itself in a political quagmire if attempts to reduce personnel or shutter facilities lead to a backlash from constituents reliant on the jobs these centers provide.

Lastly, while there is pressure for NASA to streamline expenses, the political ramifications of such decisions must be weighed against potential impacts on congressional support for space initiatives. The Trump administration’s inclination to work more closely with private industry, potentially favoring commercial partners like SpaceX, may lead to significant shifts in NASA’s operational model. However, this pivot brings its own set of challenges, given that much of NASA’s infrastructure currently exists in politically sensitive areas likely to resist downsizing. As the agency navigates these complex dynamics, the ability to successfully reform its structure and funding will require careful handling of the intricate interplay between operational needs and political realities.