On March 21, 1960, Robert Sobukwe, the leader of the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC), awoke in his modest home in Soweto, Johannesburg, ready to take part in a historic and transformative moment in South Africa’s anti-apartheid struggle. He had made plans for a peaceful protest against the oppressive pass laws, which required Black South Africans to carry passbooks in designated White areas. Accompanied by several supporters, Sobukwe walked in silence to the Orlando police station, fully expecting to be arrested for his defiance. Upon arrival, the mood outside was unexpectedly light-hearted, filled with camaraderie and support from fellow PAC members, and Sobukwe expressed optimism about the day’s events, stating, “Boys, we are making history.” However, the situation escalated as police became increasingly antagonistic towards the demonstrators.

When Sobukwe and his followers arrived at the police station, they were greeted with hostility from Captain JJ de Wet Steyn, who dismissed their intentions and warned of potential trouble if the crowd did not disperse. Anticipating a heavy police response, Sobukwe had earlier sent a letter to the Chief of Police, requesting restraint and non-violence. He outlined his planned peaceful campaign against the pass laws, expressing concern over the aggressive nature of certain policemen. Despite his appeals, tensions were running high, and unbeknownst to Sobukwe, violence erupted elsewhere in the region. By the time he was arrested around noon, at least two PAC activists had already been killed in a violent confrontation with police at Bophelong, a nearby township, foreshadowing the chaos that would soon erupt at Sharpeville.

The tragic Clashes at Sharpeville, where thousands had gathered to protest, quickly turned deadly. As the police faced an ostensibly peaceful crowd, a minor incident triggered an unprovoked shooting, resulting in indiscriminate attacks on civilians. Conflicting reports about the size of the crowd and the circumstances surrounding the shooting led to widespread misunderstanding and differing narratives; however, the factual outcome was devastating. Reports indicate that between 69 and 91 individuals lost their lives, with many shot in the back as they attempted to flee. As news of the massacre reached Sobukwe in his holding cell in Johannesburg, he was reported to be deeply distraught, feeling that the violence contradicted his pledge for an orderly and peaceful protest against the systemic injustices of apartheid.

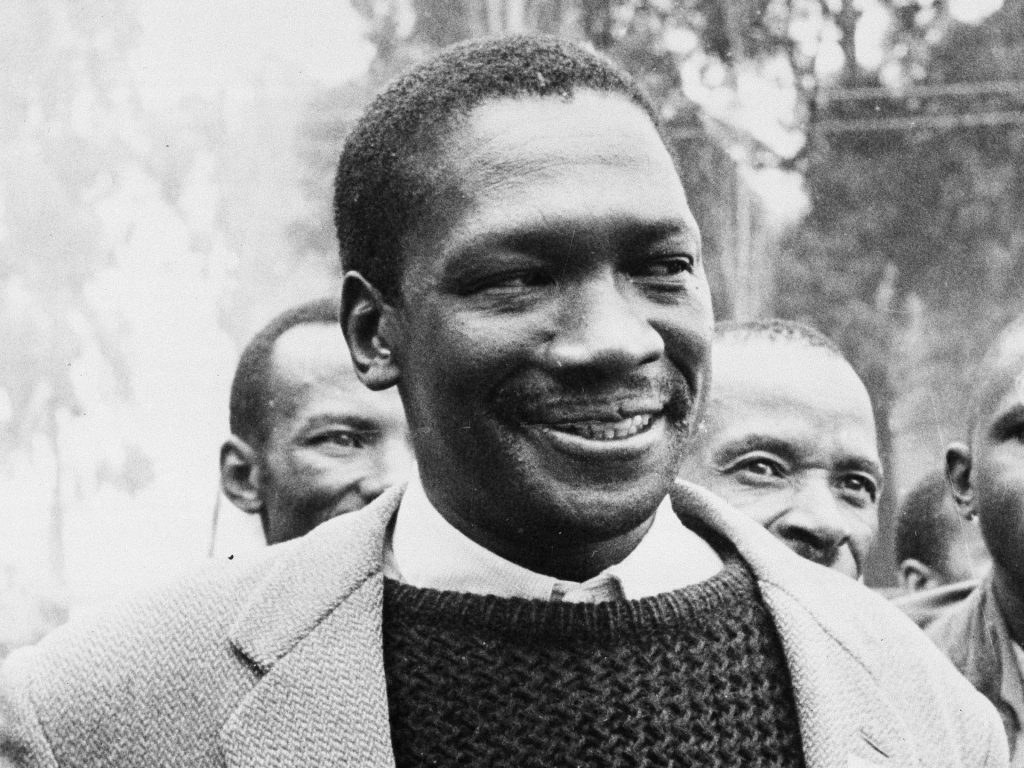

Robert Sobukwe’s early life played a crucial role in shaping his passionate commitment to the African liberation movement. Born on December 5, 1924, in a tenuous and impoverished environment, Sobukwe was raised in a family that prized education despite their hardships. His father, Hubert, made it his mission to ensure that his children received an education that he had been denied. Sobukwe excelled academically and eventually attended Fort Hare University, where he experienced a political awakening that profoundly affected his trajectory. During his time there, the apartheid regime was solidifying its power, and Sobukwe came to understand the oppressive structures that defined life for Black South Africans. Elected as president of the students’ representative council, he began to articulate his vision for an independent and united Africa, setting a tone for his future activism.

Sobukwe’s political ideology continued to evolve as he transitioned from teaching to more active involvement in the ANC. However, ideological conflicts soon arose between the ANC and a more radical movement of Africanists, who sought to prioritize the rights and needs of Africans alone. This division became critical when Sobukwe and others rejected the Freedom Charter, valuing African dominance in the struggle for freedom. As he launched the PAC in 1959, Sobukwe’s vision rested on a framework wherein liberation would be realized “for Africans, by Africans.” His inaugural speech as PAC leader underscored his commitment to this Africanist agenda while firmly rejecting colonial and interracial cooperation, establishing his legacy as one of the prominent figures of the anti-apartheid struggle.

The aftermath of the Sharpeville massacre presented both a crisis and an opportunity for Sobukwe and the PAC. The event brought national and international attention to the brutality of apartheid and marked a pivotal turning point in the liberation struggle. In the days following the massacre, there was a surge of protests within the Black community and widespread condemnation of the government’s actions. While the PAC emerged as a leading force in this context, Sobukwe and other leaders faced severe repercussions, including mass arrests and the banning of their movements. Sobukwe himself was imprisoned under the newly enacted Suppression of Communism Act, which targeted him specifically through a clause named after him, designed to prevent his release due to a perceived likelihood of continuing political activism.

Despite being silenced and confined for decades, Sobukwe’s presence endured in the consciousness of the nation, especially during the latter part of apartheid. After his death from lung cancer in 1978, he remained a figure of quiet resilience and hope within South African history. His philosophies emphasizing human dignity and non-violence resonated with activists, including influential leaders like Steve Biko of the Black Consciousness Movement. Echoing the sentiments of those who engaged with him, such as U.S. Senator Dick Clark, Sobukwe was remembered not just for his political contributions but for his unwavering belief in humanity. Even subsequent leaders of the ANC have acknowledged his concerns and beliefs, struggling to fully reconcile the ideals he championed with the ongoing realities of a deeply divided nation striving for reconciliation and understanding after decades of oppression.