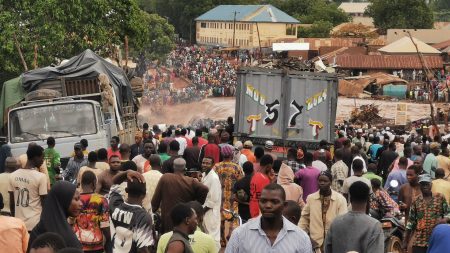

Fadzai Musindo, a 43-year-old Zimbabwean mother of three, embodies the daily struggle of many who cross the border into South Africa for economic survival. Forced by Zimbabwe’s ailing economy and the scarcity of essential goods, she works as a “runner,” transporting goods purchased in South Africa back across the border for clients. While the official Beitbridge border post presents a legal route, the associated costs and passport stamping requirements make it impractical for her daily crossings. To avoid these expenses, Musindo resorts to a more perilous but quicker route, traversing the Limpopo River with the assistance of “goma-gomas,” informal guides who facilitate illegal crossings for a fee. Though aware of the risks, including robbery and assault, Musindo finds safety in numbers, crossing with groups of women to minimize vulnerability. This informal route, however, becomes increasingly precarious with the South African National Defence Force’s (SANDF) Operation Corona, a border safeguarding operation aimed at curbing illegal crossings and smuggling.

Operation Corona, launched by the SANDF, complicates the already difficult situation for border crossers like Musindo. The operation deploys soldiers to patrol the Limpopo River border, apprehending undocumented migrants and smugglers. Although the SANDF’s efforts have reportedly reduced illegal crossings to some extent, the porous nature of the border, exacerbated by gaps in the existing fence and the seasonally dry riverbed, allows determined individuals to continue their risky journeys. The operation’s limitations, such as the inability to pursue individuals into the “no man’s land” in the middle of the river, further hinder its effectiveness. The apprehension of migrants, including pregnant women and children, raises humanitarian concerns, as families are separated and individuals are deported back to the very conditions they are trying to escape. The cycle of deportation and return, driven by economic desperation, highlights the limitations of a purely enforcement-based approach to border control.

The South African government’s intensified focus on border security, coupled with the establishment of the Border Management Authority (BMA), underscores a political climate increasingly hostile towards migration. While the government justifies its actions by citing the need to control illegal immigration and smuggling, critics argue that the rapid deportations without due process cause further hardship and may drive vulnerable individuals towards even more dangerous routes. The BMA’s efforts, which have resulted in the deportation and arrest of hundreds of thousands of people, raise concerns about the separation of families and the denial of access to legal and social support for those being deported. Furthermore, the focus on border enforcement fails to address the underlying socio-economic factors driving migration, such as poverty, unemployment, and lack of opportunities in neighboring countries.

On the Zimbabwean side of the border, efforts to curb smuggling and illicit trade have also intensified. The Zimbabwean government, concerned about the loss of revenue due to undeclared imports, has implemented stricter controls on vehicles crossing the border. These measures, while aimed at combating smuggling, create significant delays and frustrations for legitimate travelers, particularly during peak seasons. The Beitbridge border, one of Africa’s busiest, becomes a bottleneck, impacting both legal and informal cross-border activities. The interplay of these border control measures on both sides of the Limpopo further complicates the precarious lives of individuals like Musindo, who depend on the fluidity of cross-border movement for their livelihood.

Musindo’s experience highlights the unintended consequences of stricter border controls. The increased security and delays at the official border post further incentivize the use of informal, and more dangerous, routes. The longer waiting times at the border reduce her earning potential, as she relies on quick crossings to maximize the number of clients she can serve. While aware of the risks associated with crossing the Limpopo River, she often finds it the only viable option when faced with long queues at the official border post. This precarious balancing act underscores the difficult choices faced by those seeking economic opportunities across the border, forced to weigh the risks against the need to provide for their families.

The complex dynamics at the Beitbridge border crossing reveal a larger issue: the limitations of a purely enforcement-based approach to migration management. While border security measures may temporarily reduce illegal crossings and smuggling, they fail to address the root causes of migration. Experts argue that long-term solutions require a multifaceted approach that considers the socio-economic factors driving migration, while also upholding human rights and providing legal pathways for movement. Focusing solely on border control not only exacerbates the hardships faced by vulnerable individuals but also fails to address the systemic inequalities and lack of opportunities that fuel cross-border movement in the first place. The stories of individuals like Musindo highlight the human cost of these policies and the urgent need for more comprehensive and humane solutions.