The unexpected virality of a “Canada is not for sale” hat, conceived by Ottawa marketers Liam Mooney and Emma Cochrane as a tongue-in-cheek response to US annexation musings, has plunged them into the complexities of Canadian manufacturing. Their initial vision of a fully Canadian-made product collided with the harsh realities of a diminished domestic apparel industry, forcing them to navigate a landscape dominated by overseas production. The experience has been a stark lesson in the challenges of sourcing materials and production within Canada, highlighting the stark contrast between cost-effectiveness and patriotic ideals.

The quest to find a purely Canadian-made ball cap proved a daunting task. Mooney and Cochrane encountered consistent resistance from apparel manufacturers, who cited prohibitive costs and insufficient demand as reasons for their reliance on overseas production. Decades of offshoring, driven by the allure of cheaper labor and materials in countries like China, Bangladesh, and Vietnam, have hollowed out Canada’s textile industry. What remains is largely focused on specialized products like military uniforms or extreme weather gear, often incorporating imported components.

The decline of Canadian apparel manufacturing began in the late 20th century, as industries migrated to regions offering lower production costs. The cost differential for basic items like t-shirts can be staggering, making domestic competition virtually impossible. This exodus has relegated Canada to a significant importer of clothing, while countries like China and the EU dominate the export market. The limited domestic production that persists often focuses on niche markets, relying on imported materials and components to assemble finished goods.

This reliance on imported materials further complicates the pursuit of a fully Canadian-made product. Even seemingly simple items like jeans involve a complex network of globally sourced components, from rivets and zippers to specialized threads. Small businesses that strive to maintain Canadian production often face higher costs, which are reflected in the final price tag for consumers. This reality clashes with the prevailing expectation of inexpensive clothing, conditioned by years of exposure to low-cost imports. The “Canada is not for sale” hats, priced at $45-$55, reflect the true cost of ethical and domestic production.

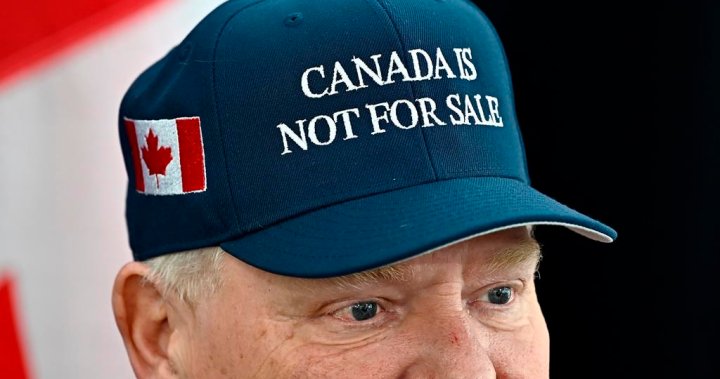

The genesis of the hat stemmed from a moment of shared indignation, as Mooney and Cochrane watched a news segment featuring Premier Doug Ford addressing US annexation rhetoric. Their spontaneous idea rapidly gained traction, culminating in a surge of orders after Ford donned the hat at a premiers’ meeting. The sudden popularity, amplified by social media endorsements and the emergence of knock-offs, forced the duo to confront the logistical challenges of scaling production. The initial made-to-order model was no longer sustainable, requiring a shift to a mass production approach.

The search for a fully Canadian-made solution continues, but in the interim, Mooney and Cochrane have established a production line in Toronto, capable of embroidering 1,000 hats per day. While they rely on imported hats for now, the experience has revealed a groundswell of support for domestic manufacturing. The overwhelming response to their product, and the willingness of individuals and businesses to contribute to a Canadian solution, has underscored a sense of national pride and a desire to revitalize the country’s manufacturing capabilities. The journey, though challenging, has reinforced the idea that when faced with adversity, Canadians stand together.