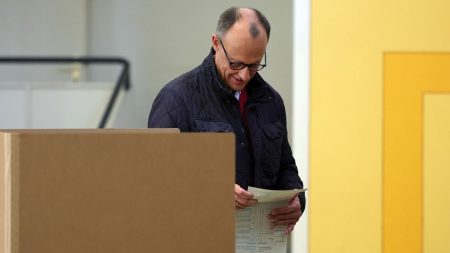

The trial of former French President Nicolas Sarkozy on charges of illegal campaign financing has captivated France, raising questions about the integrity of the 2007 presidential race and the influence of foreign powers in French politics. Sarkozy, who served as president from 2007 to 2012, vehemently denies the accusations, claiming he never received a single euro from the late Libyan dictator Muammar Gaddafi. Prosecutors allege that Sarkozy struck a deal with Gaddafi to secure millions of euros in illicit funding for his campaign, a claim Sarkozy dismisses as a politically motivated fabrication orchestrated by “liars and crooks.” The trial, which is scheduled to continue until April 10th, centers around allegations of passive corruption, illegal campaign financing, concealment of embezzlement of public funds, and criminal association, charges that carry a potential sentence of up to ten years in prison.

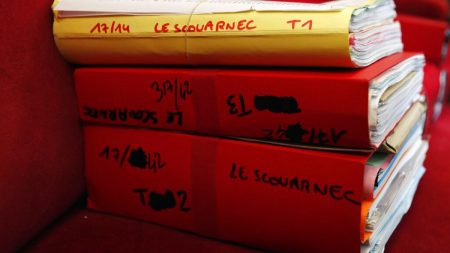

The case first emerged in March 2011, amidst the Arab Spring uprisings, when a Libyan news agency reported Gaddafi’s regime had financed Sarkozy’s 2007 campaign. This revelation came shortly after Sarkozy publicly called for Gaddafi’s removal from power, a move Sarkozy claims demonstrates the vengeful nature of the accusations. He questions the credibility of allegations emerging from a regime he had actively opposed, suggesting they are tainted by a desire for retribution. Central to the prosecution’s case is a document purportedly from Libyan intelligence services detailing Gaddafi’s agreement to provide €50 million to Sarkozy’s campaign. Sarkozy insists the document is a forgery, while French investigators have previously stated it possesses characteristics of authenticity, albeit without definitive proof of the transaction taking place.

Sarkozy maintains his innocence, emphasizing his indignation and anger at the accusations. He contends that no corrupt money flowed into his campaign because there was no corruption of the candidate. As part of their investigation, French authorities scrutinized several trips to Libya made by individuals close to Sarkozy, including his chief of staff Claude Guéant, during the period from 2005 to 2007 when Sarkozy served as Interior Minister. Sarkozy points to his successful negotiation with Gaddafi in 2007 for the release of five Bulgarian nurses and a Palestinian doctor, wrongly convicted in Libya, as evidence of his diplomatic efforts rather than corrupt dealings. He highlights the subsequent cooperation agreements signed between France and Libya in areas such as defense, health, and counterterrorism as legitimate diplomatic achievements.

The complex case involves eleven other defendants, including three former ministers, adding another layer of intrigue to the proceedings. However, two key figures are absent from the trial: Franco-Lebanese businessman Ziad Takieddine, accused of acting as an intermediary, has fled to Lebanon, and Bashir Saleh, Gaddafi’s former chief of staff and treasurer, also failed to appear. Saleh, who sought refuge in France during the Libyan civil war, later relocated to South Africa and eventually settled in the United Arab Emirates. Their absence complicates the proceedings and leaves critical questions unanswered.

This trial represents the latest legal challenge for Sarkozy, who has already been convicted in two other separate scandals. In May 2023, France’s highest court upheld a conviction against Sarkozy for corruption and influence peddling while in office, sentencing him to one year of house arrest with electronic monitoring. This conviction stemmed from wiretapped phone conversations obtained during the Libya investigation. Furthermore, in February 2022, an appeals court found Sarkozy guilty of illegal campaign financing in his unsuccessful 2012 re-election bid. While these previous convictions cast a shadow over his legacy, the Libyan financing case poses the most significant threat to his reputation and historical standing.

The outcome of this trial holds significant implications for Sarkozy’s future and the broader French political landscape. A guilty verdict would solidify his image as a disgraced politician, further tarnishing his legacy. Conversely, an acquittal would bolster his claims of innocence and potentially pave the way for a return to public life. The trial also underscores the ongoing challenges of addressing allegations of corruption at the highest levels of government and the difficulties of untangling complex financial dealings in international affairs. The case continues to grip the attention of the French public, raising questions about accountability, transparency, and the potential for foreign interference in democratic processes.