The disappearance and subsequent murder charges in the cases of Laci Peterson, Suzanne Simpson, and Ana Walshe highlight the complexities of homicide investigations, particularly when a victim’s body is missing. While law enforcement sometimes waits for the discovery of remains before filing charges, as in the Peterson case, other times, the accumulation of circumstantial and physical evidence compels them to proceed without a body, as seen in the Simpson and Walshe cases. This decision hinges on a delicate balance between gathering sufficient evidence for a conviction and the risk of jeopardizing future prosecution due to double jeopardy.

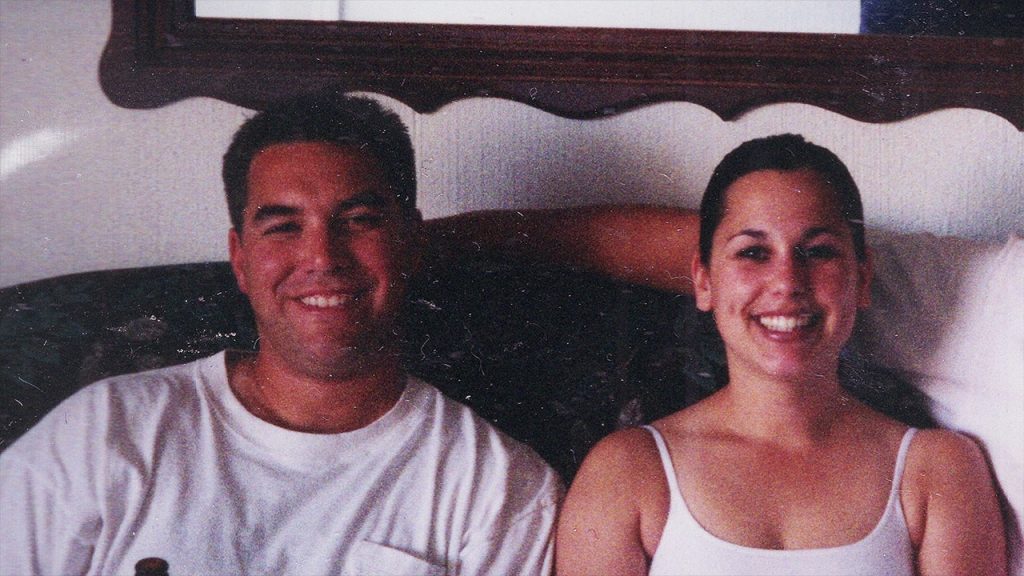

The Laci Peterson case, where her remains and those of her unborn son were found months after her disappearance, allowed investigators time to build a strong case against her husband, Scott Peterson. This delay, while agonizing for the family and the public, ultimately provided prosecutors with the concrete evidence needed for a successful prosecution. The discovery of the bodies solidified the existing circumstantial evidence, transforming a missing person case into a confirmed homicide.

However, the legal principle of double jeopardy necessitates a careful approach. The Fifth Amendment protection against being tried twice for the same crime means prosecutors have “one shot” at securing a conviction. Prematurely charging a suspect with insufficient evidence risks acquittal, even if further incriminating evidence emerges later. This explains why, in certain cases, investigators prioritize thorough evidence gathering, even if it means delaying charges until a body is found.

In contrast, the Suzanne Simpson and Ana Walshe cases demonstrate circumstances where the absence of a body did not preclude murder charges. In these instances, investigators amassed enough evidence – a combination of physical and circumstantial – to convince prosecutors that a crime had occurred and that the respective husbands were responsible. This evidence included witnesses, DNA, suspicious behavior, and the victims’ sudden disappearance without any logical explanation. The totality of these circumstances, even without the definitive proof of a body, met the threshold for charging the husbands with murder.

The Suzanne Simpson case exemplifies how a combination of witness testimony, physical evidence, and the suspect’s suspicious behavior can build a compelling case even without the victim’s remains. Witness accounts of domestic violence, Simpson’s DNA found on a saw capable of dismembering a body, and his erratic actions following his wife’s disappearance collectively painted a picture of guilt, strong enough to warrant an indictment. The absence of Suzanne’s body, while a challenge, did not prevent authorities from moving forward with charges based on the available evidence.

Similarly, the Ana Walshe case saw Brian Walshe charged with murder despite the absence of his wife’s body. While the specifics of the evidence have not been fully disclosed publicly, the circumstances surrounding Ana’s disappearance, along with Brian’s subsequent actions, led investigators to believe that he was responsible for her death. The urgency to protect potential evidence and prevent the suspect from fleeing often compels law enforcement to act swiftly, even without a body. In both the Simpson and Walshe cases, the totality of the circumstantial evidence, combined with any physical evidence gathered, pointed strongly towards the husbands as the perpetrators, justifying the decision to file charges.

Ultimately, the decision to bring murder charges before a body is found rests on the strength of the available evidence and a calculated risk assessment. Investigators must weigh the possibility of jeopardizing a future prosecution due to double jeopardy against the need to apprehend a suspect, protect evidence, and bring closure to the victim’s family and the community. Each case presents unique circumstances, and law enforcement must carefully navigate the complexities of the legal system while pursuing justice. The cases of Laci Peterson, Suzanne Simpson, and Ana Walshe illustrate the diverse paths homicide investigations can take and the difficult decisions investigators face when confronted with the absence of a victim’s body.