The burgeoning movement to create a new state, dubbed “New California,” stems from deep-seated frustration among rural Californians who feel politically marginalized and ignored by the Democratic supermajority in Sacramento. These residents believe their values and concerns are consistently disregarded in favor of policies that cater to the more populous urban centers. They point to over-regulation, the high cost of living, and a perceived disconnect between state policies and the realities of rural life as primary drivers of their desire for political autonomy. Paul Preston, the founder of New California State, frames this sentiment as a struggle against “tyranny,” arguing that California’s one-party rule operates similarly to a communist regime, silencing the voices of the rural class and imposing laws that disproportionately impact their livelihoods.

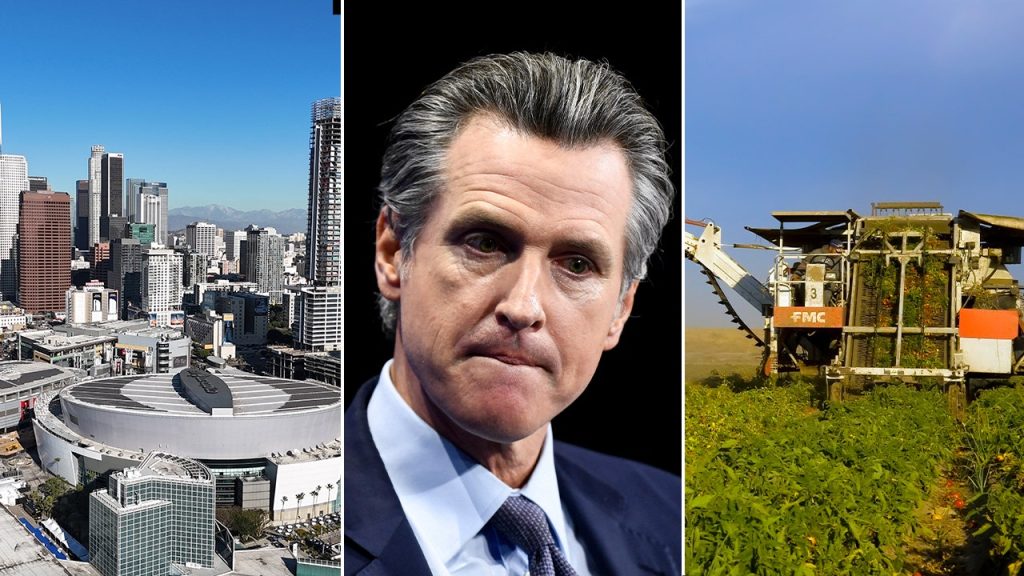

The proposed map for New California encompasses nearly all of California’s 58 counties, excluding the heavily populated urban areas like Los Angeles, Sacramento, and San Francisco. While this map is a preliminary proposal subject to change, it underscores the movement’s aim to create a state that prioritizes the needs of its rural constituents. Supporters argue that a divided California would lead to fairer and more responsive governance for areas currently overshadowed by the state’s major cities. They envision a government that addresses their specific concerns, such as border security, given the proposed state’s border with Mexico, and rising crime rates, a major grievance for many rural residents. The recent recall efforts against district attorneys in San Francisco, Alameda County, and Los Angeles County, coupled with the passage of the tough-on-crime Proposition 36, are cited as evidence of a growing statewide dissatisfaction with current criminal justice policies.

Fueling this secessionist movement is a perception that California’s political landscape is not as overwhelmingly liberal as often portrayed. Proponents point to the 2020 presidential election results, where Donald Trump won a majority of counties, primarily in rural areas, despite losing the overall popular vote to Joe Biden. This disparity, they argue, highlights the disconnect between the urban centers that dominate state politics and the more conservative rural communities. This sentiment is echoed by residents like Tina Hessong, who believes California is fundamentally more conservative than perceived and that the large urban populations disproportionately influence state representation.

California’s ongoing struggles with homelessness, crime, and the high cost of living, despite significant state spending, are further grievances driving the New California movement. Many rural residents feel that state policies, particularly those related to criminal justice and sanctuary cities, are exacerbating these problems. They perceive a lack of understanding and empathy from state leaders towards their concerns, fueling their desire for self-governance. This sentiment resonates with Republican Assembly Leader James Gallagher, who acknowledges a distinct divide between coastal and inland communities, with the latter feeling “completely forgotten” by the state government.

The New California movement reflects a broader national trend of rural-urban political divides. Rural communities often feel their voices are drowned out by urban populations, leading to resentment and a sense of political alienation. This divide is not unique to California, and similar secessionist movements have emerged in other states, including attempts to split Oregon and create a new state called “Greater Idaho.” The underlying issues driving these movements are complex and multifaceted, reflecting differing priorities and perspectives on governance, economic development, and social issues.

While the New California movement faces formidable obstacles, including the need for legislative approval and historical precedents of failed secession attempts in California and other states, it highlights the growing sense of frustration and disenfranchisement among rural communities. The movement’s leaders remain optimistic, believing that they can gain broader support, even among some Democrats, by highlighting the urban-rural divide and advocating for more equitable representation. Whether or not New California succeeds in its ambitious goal, it underscores the urgent need for a more inclusive and responsive political system that addresses the concerns of all its citizens, regardless of their geographic location. The movement’s future will likely depend on its ability to mobilize support and effectively articulate its vision for a new state, while addressing the legal and logistical challenges inherent in such a dramatic restructuring of California’s political landscape.