Recent discoveries at a lakeside in Kenya have revealed fossil footprints that indicate the presence of two early human ancestors, Homo erectus and Paranthropus boisei, as neighbors approximately 1.5 million years ago. The findings, published in the journal Science by a team led by paleontologist Louise Leakey, demonstrate that these distinct species left their marks within a short span—likely within a few days. While scientists had previously identified the coexistence of these species through fossilized remains found in the Turkana Basin, the exact dating of these fossils has always remained uncertain. However, the footprints provide a direct glimpse into a specific moment in time, underscoring the significance of this discovery for understanding our evolutionary history.

The fossil footprints in question were discovered in 2021 at what is known today as Koobi Fora, located near Lake Turkana. The research co-author, Kevin Hatala, posits that these two individuals—Homo erectus and Paranthropus boisei—were in proximity to one another and likely aware of each other’s presence. This interaction may have influenced their behavior or social dynamics in ways that are still a subject of much speculation. Such proximity raises intriguing questions about the nature of their coexistence and whether they might have shared certain habitats or resources, ultimately enriching our understanding of early hominin interactions.

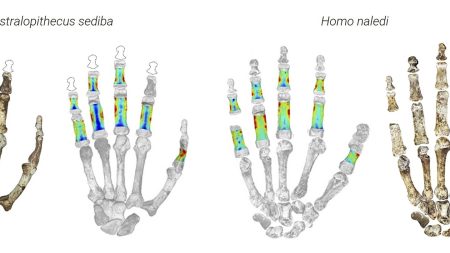

Distinguishing between the two species was achieved by analyzing the structure and shape of the footprints. Homo erectus exhibited a gait similar to modern humans, characterized by a heel-first strike followed by a roll over the ball of the foot. In contrast, the footmarks of Paranthropus boisei suggested a different locomotion style, which researchers have yet to encounter elsewhere in the fossil record. Co-author Erin Marie Williams-Hatala described how Paranthropus boisei’s foot showed greater mobility in the big toe, hinting at distinct evolutionary adaptations that set it apart from both Homo erectus and present-day humans.

Furthermore, these findings contribute to ongoing discussions about the evolutionary transition from arboreal to bipedal locomotion among our early ancestors. According to researchers, human ancestors initially had feet and hands designed for climbing and grasping, but evolutionary adaptations led to the emergence of upright walking. This study emphasizes that the evolution of bipedalism was not a uniform process, but rather a complex journey marked by various forms of gait and mobility. The notion that multiple strategies facilitated the shift to walking on two feet suggests that early humans exhibited a range of locomotor adaptations depending on environmental challenges they faced.

The implications of these discoveries extend beyond mere observations of walking styles; they invite a reevaluation of our understanding of early human behavior and interaction. Having two distinct species sharing the same territory poses fascinating questions regarding competition for resources, social structures, and the potential for cultural exchange. As researchers continue to delve into these ancient footprints, it becomes increasingly clear that our lineage is far more intricate than a straightforward linear evolution.

In summary, the significance of the footprints found at Lake Turkana lies not only in their age but also in what they reveal about the social and physical interplay between early human ancestors. This remarkable evidence of cooperation or competition offers valuable insights into the evolutionary narrative of humans and demonstrates the rich tapestry of interactions that characterized our ancestors. As scientists develop new techniques and methods to study these ancient traces, they will continue to enrich our understanding of human evolution, illuminating the various paths that led to the complex beings we are today.